The Truth about Dissident Dialogues

In early May of this year, I had the pleasure of being a part of Dissident Dialogues, a two-day conference devoted to discussing and debating “dangerous ideas,” a countercultural if not revolutionary event in today’s world. Topics included: “Why Civilized People Hate Civilization,” “Can the University Be Saved?” “Can Liberalism Be Saved?” “Is Government Censorship Ever Justified?” and “What Is the Future of Feminism?” While much of the post-event coverage has focused on a particularly heated panel titled “Is Israel’s War on Hamas a Just War?” the top draw of the conference was a highly anticipated discussion between evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and human rights activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali about the timeless question of God. Long labeled an infidel for renouncing Islam, Hirsi Ali had surprised not just her friend and sometime mentor Dawkins but also the world when she declared some months earlier that she was no longer an atheist and had become a Christian.

Indeed, I first heard of the event when Dawkins announced his planned exchange with Hirsi Ali on his YouTube channel, The Poetry of Reality. Around the same time, he posted on X: “Maybe there is still something for me to learn when it comes to religion. My dear friend and former atheist, @Ayaan Hirsi Ali has become a Christian. We will be discussing this at the inaugural Dissident Dialogues festival.” I vividly remember running to my charging phone to ring my mother. I’d inadvertently let the battery die out (something I’m prone to do), so I had to wait for the screen to light up. As soon as it did, I spastically dialed her and told her that I needed to get tickets to an event that was going to be in Brooklyn just a short subway ride from our apartment.

My exuberance knew no bounds because both Dawkins and Hirsi Ali have been wonderfully inspiring to me. Though I knew them only through their written work and recorded appearances, they taught me not only how to question the world around me with logic and reason but also to be confident and brave when I found myself reaching conclusions that stood in opposition to fashionable opinion and wisdom. I never consciously decided to be a contrarian thinker, but through them and others in their orbit, I had unintentionally become one—a high school student who’d rather spend her time reading Bertrand Russell and watching “Hitchslap” videos than creating trendy TikTok videos or scrolling through endless Instagram reels.

Even in my limited experience with the wider world outside of books and YouTube, I have long known my interests are not mainstream, especially for someone from an at times senseless, pseudo-Protestant, ersatz-woke family who attends a conventional public school in Queens, New York. If nothing else, I am self-aware. I understand my views and pursuits win me no popularity contests among my classmates, but I am also okay with this, because if I were being judged at trial, I’d like to think that they would not constitute the pool of peers from which a jury might be selected. That would be composed of the writers, thinkers, and intellectuals who have captured my curiosity and broadened my imagination—and the millions of others informed if not inspired by their work. I have had a very disheveled family dynamic for as long as I can remember—caused, in no small part, by a lack of lucid thinking and an overreliance on unevidenced beliefs. I’m well aware that rationality is a slave to the passions, to paraphrase Hume, but discovering the words of Dawkins and Hirsi Ali and so many of their counterparts was like discovering a new world—one ruled by reason and humanistic values. I know I am not alone in feeling this way. The courage Dawkins has shown over the past two decades, saying hard truths about religion that many others with his profile can’t or won’t, has served as a model for me to live authentically, and I have been brought to tears many times reading the works of Hirsi Ali. Her poignantly written memoir Infidel: My Life has both comforted and encouraged me. When she writes about her beloved sister, Haweya, I cannot help but picture my own sister. Figures who have risen to prominence more recently, such as the young but relentless journalist Lee Fang, have also been fantastically motivating for me. Although I was not exactly sure what to expect from the conference, I knew it would be my chance to finally be among each of these individuals and many others whom I had only ever seen or interacted with through the two-dimensional filter of a screen or leaf of paper. I simply couldn’t miss it.

Around a week after tickets went on sale, I got a text from my mother saying that she had secured a ticket for me. I spent the next few months reminding myself that it's okay, that whatever hardship or worry or conflict or judgment I was experiencing that day would pass, and that I was a bit closer to being in an environment where I would be able to be myself and have honest dialogue without fear or judgment. I knew that the expense had made a dent in the wallet of my hard-working single mother, but knowing that my interests and views have made me a bit of an outsider in my school and neighborhood, she was equally excited for me to attend. Three days before the event, I sent an email with a modest request to the address listed on the official Dissident Dialogues website. I explained how many of the planned speakers had positively impacted my life, and I wrote that I really wanted to bring my dear mother along so that she might experience the event with me. After all, the speakers scheduled to be at Dissident Dialogues had also impacted her. Even if she had ideological differences with many of them, she valued the notable effect they had had on me. I was delighted when Dissident Dialogues offered to provide us with a free ticket so that my mom could come along with me.

On day one, after settling into our seats, I noted something special: at an event driven by ideas, there seemed to be no divide by ideology. I saw people from various diverse demographics. I don’t really have any friends my age, so I was particularly glad to see just how many young people were there! My mother tapped my shoulder and motioned to our left, stating, "Look, there’s Alex O’Connor. You should go over and talk to him!” At that juncture, I did not. I did feel slightly out of place—no fault of anyone or anything besides my own insecurity—but after some contemplation, I realized that the point of this event was to challenge such feelings. It would be terribly ironic for me not to express my ideas at an event meant to be a place for

“dangerous ones.” During the first break between panels, I went outside to get some complimentary coffee provided by one of the event sponsors, Ground News. I made sure to leave the stage area ten minutes before my fellow attendees to ensure that I would not have to wait in any long lines. When the panel finished and I had some caffeine in my system, the real excitement began.

As I waited for my mother to join me outside, I spotted someone whose book I had been discussing with my chemistry teacher not too long ago. The book in question is Enlightenment Now, and I had championed Steven Pinker’s thesis that we have made great strides as a species thanks to science and reason, while my proctor took a more Chomsky-esque approach to the idea of moral and material progress. The general idea that the world has become a more livable, safer, and better place is something that fuels me every day and informs my views on current events and social issues. Not wanting to miss this opportunity to tell Pinker how inspiring I find his ideas, I walked over to him. His calm demeanor made him approachable and easy to speak with. I briefly mentioned how I commonly cite his work, whether I’m speaking with faculty at my school about the news or trying to console others my age who are disheartened by the state of the world. While it is a positive that today’s youth are very aware, being constantly bombarded with information is also detrimental to our well-being. We engulf ourselves in social media, and because there is so much bad out there, it can be easy for us to be distracted by all of the good. As a result, many young people today are misanthropic and depressed. I told him how grounding myself in his clearly expressed and accessibly communicated ideas helps lift this sense of pessimism and unease. After I thanked him, and, in turn, he thanked me for enjoying his work, we posed for a selfie.

At lunchtime, while eating tacos from one of the food trucks on-site, I had a great conversation with a middle-aged white man from out of town. We spoke about the stifling of open communication and the echo chamber that I often find myself in as a young person, because others my age often have very clear ideas about acceptable questions and terms of discussion. I felt that this guy was genuinely interested in my experiences and views. Engaging in in-person discussions with complete strangers well outside my demographic is not a regular part of my life, so I was a bit insecure at first, but a few minutes into our conversation, I began to feel more confident. I knew that I was surrounded by people who disagreed with me on various matters, but still, I felt at home intellectually. My expectations for the event were more than being met. With a new panel about to begin, I threw out my trash, said goodbye to my chatting partner, and scurried back inside.

Over the course of many panels, it occurred to me that the formatting was more conversational than I had expected. I had anticipated more heat, but to my pleasant surprise, even when disagreements came up, there was very little acrimony. There was a common consensus that I noticed with every person with whom I spoke: free dialogue is being suppressed across society. Whether I was speaking with a fellow attendee about the position of minorities in various countries or with Kathleen Stock about the hostility toward unpopular opinions on campuses, this was a regular refrain. Outside of this general opinion, I heard many varying positions. If I had to characterize the overall political bent of the speakers and attendees, I would say they were slightly to the right, but the event was not ideologically exclusionary—maybe only to those allergic to offense—and the diversity of thought among those present was readily apparent. While I find the political compass to be dichotomous and fallacious, what is frequently identified as the Left has become a hyper-sensitive cesspool—and I say this as someone who identifies as “left of center.”

The ideological diversity of those in attendance became abundantly clear to me during one of the afternoon breaks. I was standing outside, speaking with my mother while looking at the scenic backdrop of the Brooklyn Bridge, when I turned around to see Alex O’Connor walk past. He is one of my favorite YouTubers, so I am sure my approach was awkward, but Alex was super amiable and kind, and we spoke for about an hour. We touched upon Jesus, objective morality, free will, and much more. The feeling of being welcomed and relaxed only increased as the conversation evolved and deepened. Given the easy-going and convivial environment at the event, other individuals joined the conversation. There was a mix of voices and perspectives. The feeling of belonging and chillness only further developed when my mother—once a devout (now less traditional) Christian—came with drinks in hand.

When it was time for the next session to start, I was not too interested in the topic of discussion, but this highlights something fantastic about Dissident Dialogues and the physical space it occupied. If an attendee was not particularly fascinated by the present panel, they could roam around and converse outside of the main stage area, whether outside at a picnic table, in a lounge area, or next to the coffee stand or one of the food trucks. That is precisely what I did!

I eventually stopped by a vendor table populated with books. A number of titles caught my eye, including Emancipation of a Black Atheist and The Ebony Exodus Project: Why Some Black Women Are Walking Out on Religion—and Others Should Too. These were unexpected but welcome finds for a half-black atheist. I learned that the vendor was Pitchstone, a publishing house dedicated to advancing Enlightenment values in the modern day, and I had the pleasure of meeting the company reps, including one of Pitchstone’s authors, filmmaker Onur Tukel. Along with other book browsers, I spent the next hour or so discussing various authors, current events, sexual liberation, the war in Iraq, Hitchens, the difference between Turkish and Greek food, and so much more. (The time I spent at the table and the contacts I made there are also how I came to write this very article!)

This sense of camaraderie and belonging continued and grew even larger into the second day of the event. I spoke with an extraordinarily wise and talented group of ladies while fixing my lipstick in the mirror of the dimly lit chic bathroom. I bonded with the young and stylish political commentator Amala Ekpunobi as we stood face to face. When she had waltzed into the Duggal Greenhouse she had commanded a sense of attention with many eyes on her. Despite her head-turning elegance and VIP status, Amala was lovely and warm, taking a considerable amount of time to chat. In mentioning how I admire her candidness in voicing her views, I pointed out that I don’t agree with her on everything. The variance in our sentiments was something she appreciated.

Although I greatly valued the panels and speakers I heard, the chance to converse with those whose work I have long admired and to connect with other curious if not like-minded individuals was a pivotally important and moving experience for me. Perhaps the most memorable moment of the event for me was when I finally had a chance to meet the person from whom I first learned about the gathering, Richard Dawkins. I do my best not to put anyone on a high pedestal, but I do admire some people more than others. Like many of the conference speakers, Dawkins sat in the audience for more than a few discussions. During one of the panels, he happened to sit one row ahead of me. To be in a space with the person who helped give me confidence and a voice to break away from thought-killing subservience and the stifling pain of religion was nothing short of astonishing. Afterward, I meekly walked up to Professor Dawkins and prefaced my request for a picture with an apology for my awkwardness. He was wonderfully kind, and his assistant offered to take the picture for us. Although he said little, Dawkins listened to all I had to say. I mentioned how, not too long ago, when my family would speak of God, I would feel strange and sometimes felt obligated to be quiet. Dawkins humorously responded, “You? Quiet?” We both laughed!

By the time the inaugural Dissident Dialogues came to an end, I had learned many valuable lessons. The first and most important is that people are more or less similar, no matter whether a world-class thinker who’s written a shelf full of bestselling books or a high school student in New York from a single-parent home. After all, we are all just primates. I experienced no nastiness or judgment from anyone I interacted with at the conference—whether public intellectual or private citizen—even from those with whom I disagreed on subject X, Y, or Z. Although I wouldn’t have guessed it at the time, perhaps the greatest lesson for me came after the event, when the need for open, honest, and authentic dialogue without fear of being smeared or outcast from polite society became starkly apparent. This lesson hit home in two ways.

First, I was pleased to see one of the teachers from my school at the event, but when we returned to school on Monday, she was hesitant to tell anyone about it. When asked about the event by a colleague, she was too anxious to mention it by name and only said it was “very controversial.” Second, more than a week after the event, I came across an article about it in the New Republic titled “The Anti-Woke Grifters Get Their Tithe." I can only describe the piece as sneering—the type of article that was written in the author’s mind before the event even took place. Indeed, my experience contradicts just about every line written by Raina Lipsitz.

Much of the piece is an attack on one of the event’s two organizers, musician Winston Marshall, formerly of Mumford & Sons, but Lipsitz starts her scathing critique by attempting to downplay not only the size and significance of the event but also the choice of venue and staging (which, to her, was “more Texan than Brooklyn”). She writes, for example, “According to Marshall, around 800 people were there. (It looked more like 400 to me, but the crowd was dwarfed by the venue . . .).” Throughout the piece, Lipsitz seeks to discredit Marshall in the eyes of her target readers: (1) she recounts how he sent “a congratulatory tweet” to “right-wing influencer Andy Ngo,” and (2) she makes a point of saying that his father has “a long history of criticizing Islam and funding right-wing and/or Christian causes.” She is also apparently a mind reader. According to Lipsitz, Marshall would “rather be a rock star with a massively successful band than the guy who quit the band to write pointless op-eds condemning the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement,” and she speculates that “he organized Dissident Dialogues to stay in the limelight.” A reference to Rupert Murdoch even gets shoe-horned in for good measure. Might it simply be that Marshall actually believes what he says, is exercising his right to say it, and wants others to have the right to do the same? Notably, Lipsitz conveniently fails to mention the other organizer of the event, Desh Amila.

Unlike Lipsitz, I don’t want to mind-read, but I’m not sure how she could have missed Desh, if other than perhaps because his presence interfered with the story she had prewritten? After all, when Marshall first went on stage, Desh was standing right next to him, was prominently listed on the event program and website, and took to the mic at various points throughout the event. While I did not have the opportunity to speak with Marshall, I did chat briefly with Desh, who, throughout the event, busily ran to and fro to ensure the event ran smoothly and seamlessly. My mother actually thanked him for organizing the event, telling him how reason, philosophy, and discussion have so profoundly aided in improving my quality of life. Not to be dramatic, but she is absolutely correct. Even so, it wouldn’t have been easy for my mother to say this to him, because that first day, Desh was wearing a t-shirt that read simply: “Hitchens & Dennett & Dawkins & Harris.”

You’d think in such a disdainful review of an event, there’d be enough ink in the author’s poisoned pen for both organizers. Why doesn’t Desh get mentioned even once as “an organizer of poorly attended anti-woke festivals,” which is how Marshall is described in a photo that accompanies Lipsitz’s piece? Her entire article only bolsters the argument that so much of the media cares more about identity than actual ideas—and far too often relies more on scare quotes than on accurate quotes. Marshall did not make his Christianity a part of his talking points at the event but instead emphasized that all he wanted was open dialogue. This isn’t to say that identity isn’t important. Indeed, human rights activist Jewher Ilham emphasized the identity-based oppression that the Uyghur Muslim minority faces. She repeatedly noted the lack of religious freedom faced by Muslims in China, yet, in this clear case where the subject of “identity” does warrant discussion, Lipsitz does not name Ilham in her piece either. Rather, she simply refers to Ilham’s session “The Uyghur Story” in a list of what Lipsitz refers to as the event’s “confused and disparate topics." The multiplicity and range of topics and speakers was not a bug of Dissident Dialogues but rather a feature—a plus—reflecting not only the vision of the event but also the sheer number of important topics on which open debate and discussion have been missing. The event was never intended to be hyper-focused on any one topic but rather was designed to be a forum for dialogue across divides, and the panelists were intended to spark conversation.

Lipsitz seems to not understand that ideas are meant to be shared and that people can change their minds and constantly seek to do so. She also puts people in neat boxes, like a Mean Girl who describes the various cliques at her high school in a teen dramedy. Consider, for example, how she describes attendees: “Sartorial choices ranged from jeans, T-shirts, and athleisure to business casual to full-on Fox News power babe—think Jay Roach's 2019 movie Bombshell.” (Might this be a new fallacy? Guilt by wardrobe perhaps? For those who might not be aware, Bombshell stars Charlize Theron playing Megyn Kelly, Nicole Kidman starring Gretchen Carlson, and Margot Robbie playing a composite of women at Fox News subjected to sexual harassment by Roger Ailes, played by John Lithgow.) Given Lipsitz’s grumbling about “anti-woke” identity, you would imagine that she would respect self-expression and self-identity more, but she goes on to quickly dismiss the manner in which her fascination—Winston Marshall—characterizes himself. Demonstrating more of her mind-reading abilities, she writes, “The younger Marshall insists that he is not a conservative and claims to be equally repulsed by ‘political extremism’ on the left and the right. . . . He holds a hodgepodge of often contradictory right- and left-wing views, which in his mind make him a free-thinking radical.” Consider the hubris and myopia it takes to write such a sentence. If Muslims don't have to exist in the box of fundamentalism—a position I imagine Lipsitz holds—then Marshall, as a Christian, can hold views that may seem odd for the stereotype of a Christian.

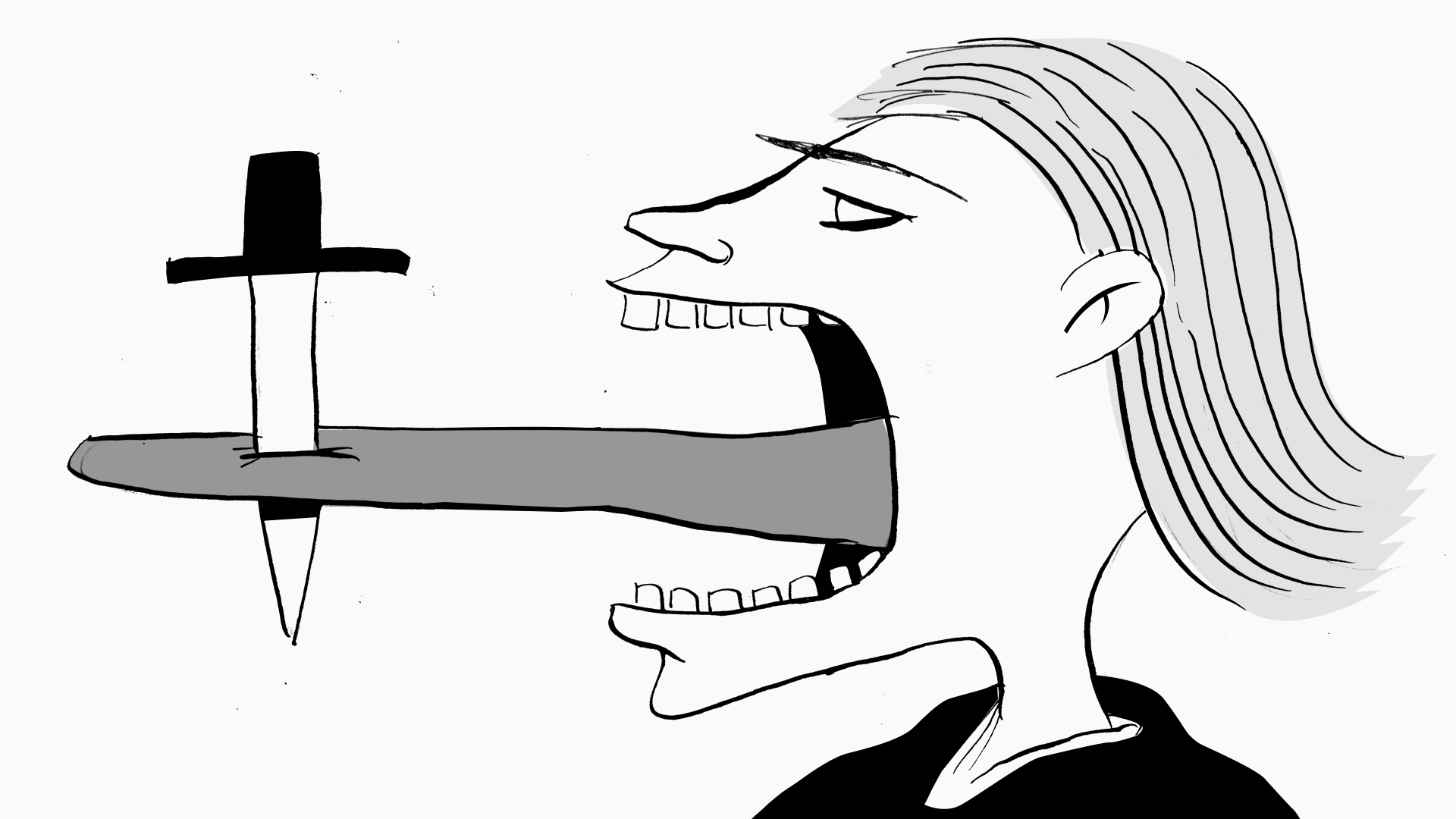

My mother (and most Christians, for that matter) don’t exist in a monolithic, doctrinal-focused bubble. Perhaps Lipsitz herself has spent far too much time in Brooklyn, and might herself benefit from a trip to Texas? At the very least, she should have read up a bit about the speakers she’s condemning for selling “snake oil.” (She readily admits she “had only heard of a few of the speakers beforehand.”) When reading her article, I realized that she is, at best, ignorant and, at worst, malicious when conveying information about the event. For example, she writes, “As comedian Bridget Phetasy pointed out during her set, only one of the speakers had ever faced a life-threatening consequence for dissenting: Masih Alinejad, an Iranian who lives in Brooklyn and has been threatened with assassination for criticizing the Iranian government.” When I watched the event live, it was clear to me that Phetasy was exaggerating for comedic effect—you know, as comedians do—and not expressing a fact about all of the speakers. I imagine all of the other laughing attendees perceived Phetasy’s joke similarly. However, Lipsitz frames this wisecrack as if it’s some kind of truth. Anyone remotely familiar with Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s story knows that Alinejad is not the only one to have faced real threats to her physical safety. Hirsi Ali knows what it’s like to live in discreet hideaways, to travel secretly, and to be forced into a security dungeon for her “dissident” views. Her friend, film director Theo Van Gogh, was slaughtered in the streets of Amsterdam in 2004 by an incited maniacal terrorist. It is worth noting that his murderer pinned a five-page letter to Van Gogh’s stomach with a knife. It was addressed to Hirsi Ali. The message was abundantly clear: you’re next.

It’s no secret that Dawkins has himself been the target of threats and is likely no stranger to bulletproof vests. To get a sense and scale of how much contempt he endures, just watch him read hate mail. While it does stimulate a good laugh, people really do abhor Professor Dawkins! Even though Dawkins personifies much of what Lipsitz’s audience presumably loves to hate—old, white, straight, hetero (continue with banal descriptive utterances) men—as I walked around the event, I met countless people looking forward to seeing Dawkins—something not unexpected given he and Hirsi Ali were the closing panel. Yet, Lipsitz chose not to make reference to anyone whose life has been positively impacted by Dawkins. Rather, she reports, “Ahmed Almadlouh, a 36-year-old graduate student at Columbia University, told me he'd heard about the conference from a friend who admires Richard Dawkins. (Almadlouh said his initial thought was, ‘Isn't [Dawkins] that old racist atheist?’)” This quote, among others littered throughout the piece, reveals Lipsitz’s overall journalistic strategy. Why make a cogent argument or present meaningful evidence if you can find someone in attendance who will say what you want them to say—or at least offer a line that you can selectively, if not cynically, quote? I wish she would have asked me what I think about Dawkins and the other speakers. I would have told her that I think he is brave, and for that matter, my Jesus-loving mother agrees!

But I also know that even if she had asked us, she would have made us out to be duped rubes—hapless victims of soulless grifters. Indeed, as someone long nauseated by the way in which people like Lipsitz dehumanize and essentialize people based on their skin color or gender—people like me assumed to have no agency or ability to resist our presumed oppression—one distinct passage from her really aggravated me. Describing a scene she witnessed involving two attendees, she writes, “A tall young Black woman in rectangular glasses, a gold chain necklace, and a black lace maxi dress noticed Sam [a 19-year-old Lafayette College student], who is white, before I did. She began loudly berating him for his choice of reading material. ‘The God Delusion?’ she said disdainfully. ‘Do you really think we’re animals? Is that what you think we are?’"

First, I highly recommend that this fellow attendee humble herself and consult some evolutionary science. Being an animal does not make you a barbarian; it does not make you awful. Only according to verses like Isaiah 64:6 are we tinged with the grime of humanness! Second, it is concerning that Lipsitz describes the appearance of this black woman in such detail but does not do the same when describing anyone else at the event. It’s almost as if she is trying to build a narrative around identity-based stereotypes and not evidence-based ideas.

After the panels came to a close and most of the crowd had left, speakers and attendees alike had a final chance to socialize at a post-event party sponsored by Third Rail. There, I held the drink of the hysterically witty Australian comedian Tom Nash, who shared a hit of his vape pen with my mom as he showed me how he DJs with no hands and just hooks. This will be singed into my brain for the rest of my life as one of the coolest experiences ever! Like Nash, I know that life is the only option, but a few years ago, I truly thought that I would have to live disingenuously—to lie about who and what I really am. For the first time at Dissident Dialogues, I encountered others like me who have similarly exited the cave of groupthink.

For Lipsitz, all of this might mark me as a source of pity—just one of four hundred (by her count) earnest dopes who paid $299 or more for whom she feels “indignant on their behalf”—but I reject her patronizing indignation. She might not be able to conceive why someone like me would pay hundreds of dollars for a two-day event on ideas, but I would gladly pay the admission price again—and I’m sure my mother would again oblige. Some might save for Taylor Swift or the Knicks, while others might break their piggy bank for Dawkins and Hirsi Ali. No shade to Swifties or Knicks fans, but I’ll take the latter any time. I was welcomed and accepted—even among the “VIPs”—and unlike Lipsitz, I managed to discover that these “anti-woke grifters” are actually really nice people who believe what they say and, indeed, aren’t grifters selling “snake oil” at all. Even if they might have differing prescriptions for what ails us—they are at least willing to discuss differential diagnoses and consider the merits of different treatment options! Discussion is the only way the widening ideological ridge across society can be bridged, whereas Lipsitz’s hit piece serves only to jam one more wedge into the growing crevasse. If she can resolve her revulsion and contempt for Dissident Dialogues and muster up the courage to return next year, I would love to hear from her in the flesh and have the opportunity to challenge her on her obvious blind spots and prejudices. She clearly has a strong point of view, and that’s all good, but the fallacious and skewed storytelling is not. Even so, I imagine there’s some common ground to be found. In fact, I hope Desh and Winston give her a chance to express her opinions at next year’s event!

Either way, I intend to be in the crowd.

Emma Muniz is a high school student in Queens, New York. More of her writing can be found on Substack.

August 2024