I Have No “Driving While Black” Stories

Back in February 2014, a good friend invited me to deliver a presentation as part of a Black History Month panel before a lunchtime gathering at the University of California, San Diego. The general topic was “Fifty years ago, a landmark Civil Rights Act promised to transform America. The UC San Diego Library presents a scholarly panel discussion on the legacy of that act and the state of civil rights today.” Three black UC San Diego professors served on the panel, and I was there in my capacity as a former law professor. I argued that there were obvious gains under the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and we should be thankful for the better world we live in. I even compared the treatment of a black motorist in San Diego in the 1940s with the college road trip we took with our boys in 2013. I had no “Driving While Black” stories. I relayed stories of wonderful road trips to Stanford and Yale.

Here’s a recap: It is time for the college road trip. My eldest son is applying to college. I rent a car for the long trip up to the Bay Area and back. We pack snacks because we want to save money, not because of a Jim Crow world. We drive up the 5 through Orange County and Los Angeles. We got a late start, so we are traveling at night through Ventura County and on up the coast to Santa Barbara. I love Santa Barbara, but it is dark when we arrive. We check into this coastal motel and crash. The next morning, we check out the best breakfast place in Santa Barbara. While we are there, my eldest son meets Bruce of the Beach Boys. Bruce shares breakfast with us and urges my eldest son to apply to college in Australia. Very cool moment. We then hit the road and travel a long drive up to San Francisco and the University of San Francisco (USF). A black tour guide attempts to sell my son on USF. We then drive across the Golden Gate Bridge, frolic in Sausalito, and spend the night in Danville, one of the most affluent communities in the state. We stay at the Best Western Inn. My eldest son roams around town. He convinces me to have dinner at this vegan place. We do, and he concludes it is too hippie. We then cruise down to the University of California, Berkeley, have lunch at this football-themed restaurant chosen by my son, and then it’s off to Stanford. We eat dinner at this upscale restaurant that caters to venture capitalists and Silicon Valley types. The boys love the place. We get a late start going home, and I just can’t make it back to San Diego. We find some motel in the middle of nowhere and crash. We buy gas in Ventura County and eat fast food at McDonald’s. Then we head home.

Later that summer, my wife takes our three kids on a college road trip back east. They fly into a small town outside of Princeton, New Jersey, and stay with my wife’s cousin, who has three beautiful biracial children. The next day, my wife takes our teenage boys to the Big City, Manhattan, to tour New York University and Columbia. The next day, they drive to Yale to visit my wife’s old college. My son, a Yale legacy, has an admissions committee interview. Then, it is on to suburban Maryland where my wife and the kids stay with my wife’s sister, a Harvard College graduate, and her husband in an affluent suburb of Washington, D.C. The next day, my wife and kids are off to the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. They do fast food and eat at a nice soul food restaurant in Richmond, Virginia, chosen by my sister.

I am old enough to have attended an all-black segregated school in the South, and these are my stories about driving in today’s United States.

The other black professors piled on me like a ton of bricks. How dare I share my pleasant reality as a black dad on the road with my kids? As my friend later put it, she had “never seen a panel get quite so very animated, as generally most of the folks around here agree with one another.” And that’s the danger of the echo chamber in the academy nowadays. I literally tried to engage my fellow panelists as they ran away from me in fear and horror. I face radical politics at home, so I was aware that too many black people major in the minor. There are obvious gains under the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but for some reason, fear pervades black culture and consciousness. Small incidents are always blown out of proportion to scare black kids and adults too.

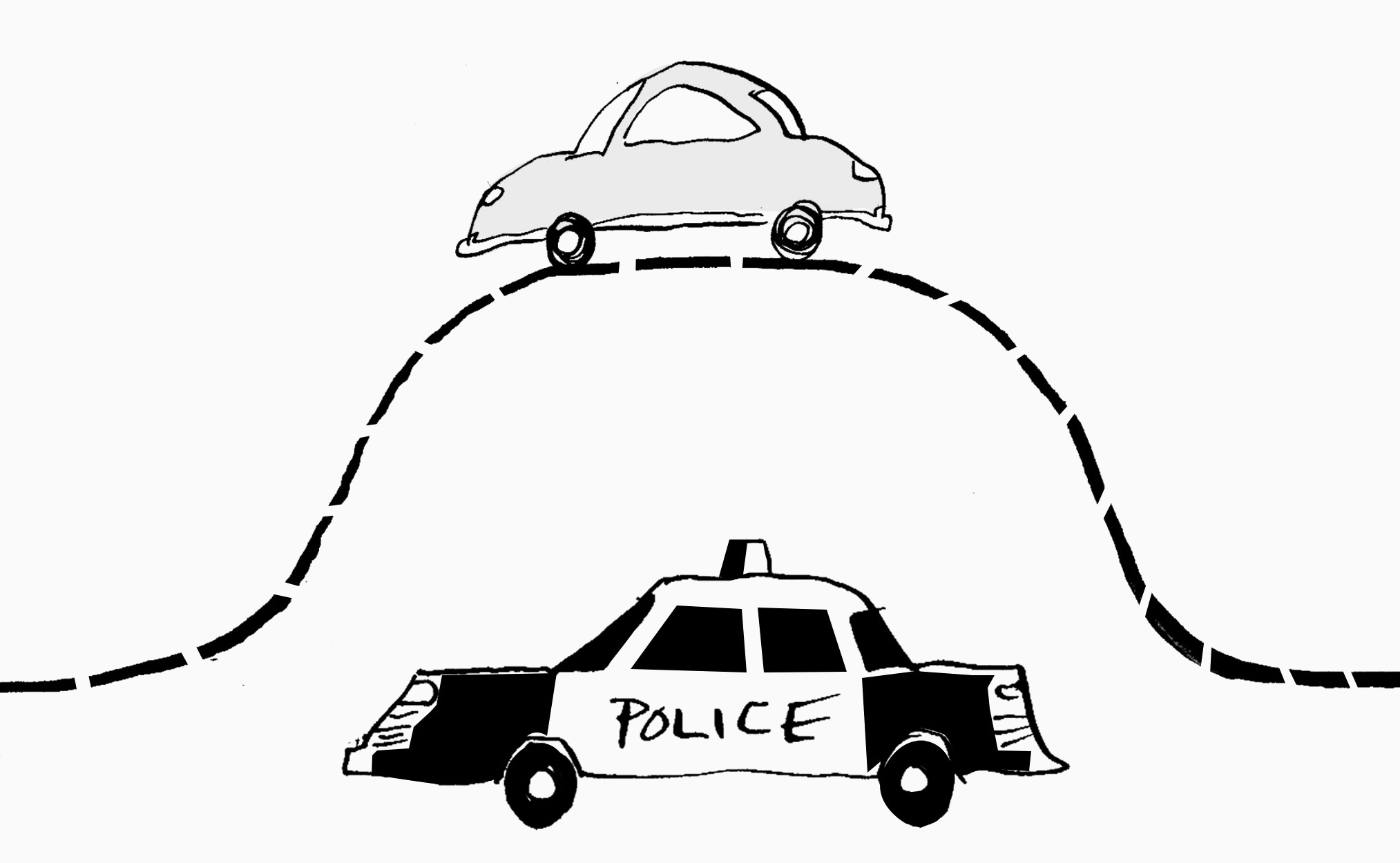

I have no Driving While Black stories. I have several driving-while-stupid stories.

My friend “Julia,” an immigrant to the United States from Hong Kong, has a Driving While Black story worth sharing. One recent afternoon, I received a frantic text from her. She was distraught — “My employer is putting me on a ninety-day performance improvement plan and suspending me for the Driving While Black thing.”

What Driving While Black thing? A few months earlier, Julia had met with two African American members of the public as part of her job. The meeting was standard and unremarkable until, a few minutes into the conversation, one of the individuals, a male, said he was nervous about driving across the country due to a fear of Driving While Black. Julia thought that having such a fear in today’s world was over the top, and she said so not out of disdain but out of compassion. Julia had known struggle in her life and felt his Driving While Black fears were overblown. The guy should not feel more afraid than someone of any other race. The man was so fragile when confronted with reason that he filed a complaint against Julia with her employer. Now Julia’s career is in jeopardy, and all because an irrational person had to be coddled.

Might it be the panelists ignored and dismissed my experiences because they thought I couldn’t relate to the plight of black Americans who are stuck in a cycle of poverty — who don’t have the opportunity to take their kids on college tours?

No, I don’t think I was ignored or dismissed because my story was seen as an outlier. After all, only a minority of black Americans are impoverished — back in 2014, 26.2 percent of black Americans were “stuck in poverty,” to use popular phrasing, while today, it’s 17.1 percent. So, we’re talking about a minority of black Americans. Further, we were all black professors, current or former, and nearly four out of every ten black eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds are enrolled in college. I was ignored and dismissed because my words did not subscribe to dogma.

What is dogma? Today, any public discussion of the Black Experience is supposed to be about oppression. And when I say “any public discussion,” I mean just that. Public discussions include, but are not limited to, lectures, panels, speeches, opinion pieces, news stories, interviews, diversity training, and social media posts. Consider the general absence of viewpoint diversity and the consistent oppressor-oppressed framing of race in any public discussion you might come across. As one young family member once told me, “Blackness is oppression. Nothing else matters.”

How could a member of my family believe nothing else matters about blackness but oppression? It would be one thing if this person had grown up poor in a public housing project with no dad and a mom strung out on drugs and older brothers in prison. Maybe then I could understand their perception of the world. But this is far, far from the case. This person is privileged to live in a wealthy coastal town, to be the descendant of the first black congressman, and to be the child of Ivy League–educated parents with good jobs. In what alternative universe can this family member fervently believe blackness equals oppression and nothing else?

But why wouldn’t this family member think that? After all, that’s the only message today’s younger generations have ever heard, whether on their televisions, on their smart phones, in their earbuds, or at their schools. Imagine if we practiced a little diversity, inclusion, and equity in how we talk and teach about the Black Experience.

For example, in what recent public discussion about race have we ever heard mention of black individuals like John Mercer Langston (1829–1897)? How many schools, companies, and nonprofits that actively promote books by Ibram X. Kendi, Robin DiAngelo, and Ta-Nehisi Coates have ever recommended his autobiography, From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol? He did not begin his life story bemoaning white privilege. He did not commence his life story blaming others or the system. He introduced his life story with a simple and universal message: “Self-reliance [is] the secret of success.” He chose his words with care. Langston was sixty-four years old when his autobiography was published. By that point, he had pioneered student success at Oberlin College; been rejected from law school because of his race; trailblazed triumphantly as the first black lawyer in antebellum Ohio; served as the General Inspector of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, the founder and organizer of the law department at Howard University, the Acting President of Howard University, the Minister to Haiti, and the first President of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (now Virginia State University); and been voted in as the first black congressman from Virginia.

In telling his epic life story, he makes no mention of institutional racism or structural racism or white privilege.

Did Langston not understand oppression?

To ask the question is to answer the question. If blackness is oppression, Langston knew blackness as oppression up close and personal more so than any living person in the United States can possibly know oppression today. Langston’s own brother, Charles Langston, was incarcerated for his opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act, and Charles thundered against the Fugitive Slave Law with an eloquence worthy of the ages. Those who today scream oppression at the smallest perceived slight dishonor the memory of courageous heroes who fought honest-to-goodness slave catchers in the back alleys of northern cities. There is something offensive in equating the oppression of a captured free black returned to slavery with the arrest of two black men at Starbucks. There is no moral equivalence here.

If Langston understood real oppression during real slavery, why does he begin his life story with self-reliance as paramount, as the secret of success? Langston tells us why. Self-reliance fitted Langston mentally and morally for those trying and taxing duties that awaited him in life. “Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist.” Self-reliance is the importance of avoiding conformity and following one’s own ideas and instincts. Truth is inside a person, and this is authority, not institutions.

Do what you think is right no matter what others think. Truth is within oneself. Reliance on one’s own efforts and abilities will see one through.

This is how Langston understood the world and himself.

Psychology professor Martin E. P. Seligman, in his book The Hope Circuit, speculates that the words running through our heads may correlate with psychological health and well-being. In relating his life story, Langston used these words the following number of times:

Success—103

Opportunity—70

Church—65

Beautiful—47

Blessings—7

Blessed—6

Greatness—5

What about the words often used by those with high neuroticism, words like sick, hate, depressed, depression, stupid, and nightmare? Langston did not think of the world in these terms:

Sick—7

Hate—4

Depressed—0

Depression—0

Stupid—0

Nightmare—0

In a time of unimaginable racial hate to the modern mind, a black man gave “hate” bare mention in his 534-page life story!

Consider how today’s so-called experts on race — the ones so often called upon for comment and endlessly cited in public discussions — describe the world. Using Ta-Nehisi Coates’s iconic Between the World and Me as a prism is illuminating. A man born in 1975 in Baltimore, Maryland, over the course of his 176-page letter to his son, uses the word “hate” when describing his life almost (but not quite) twice as much as a man born on a Virginia plantation in 1829. Who is more neurotic about race in America? I would place my bet on the writer who never graduated from Howard University in lieu of the first black Acting President of Howard.

This is the uncomfortable truth about race in modern-day America. Conditions are so blessed today that writers must tip over into unhealthy, unbalanced positions and arguments to make a splash.

I don’t do dogma or performance art. When I present about black history, I lean into authenticity. Why would I deny what I know as plain truth? We are blessed to no longer give segregation in public accommodations a second thought. In keeping with today’s public discussions about race, my co-panelists were closed-minded to the blessings of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And so, they were caricatures—hear no blessing, see no blessing, speak no blessing. The dogma about race that has taken root is the problem, not a lack of empathy or a denial of reality on my part.

Should I lie and say, “Yes, I have been pulled over for Driving While Black — that yes, I am oppressed”? Is it better to lie so that one will be embraced by fellow black professors and approved for participation in public discussions about race?

That is the question I put to you.

This essay is adapted from letters the author wrote to Jennifer Richmond, first published in the book Letters in Black and White: A New Correspondence on Race in America, which is available for purchase at these paid links: Amazon, Bookshop, and Pitchstone.

Winkfield Twyman, Jr. is a writer and former law professor who seeks understanding across the color line in America. Born in Richmond, Virginia, he currently lives in San Diego, California.

July 2024