Today’s Left Needs to Learn from Christopher Hitchens

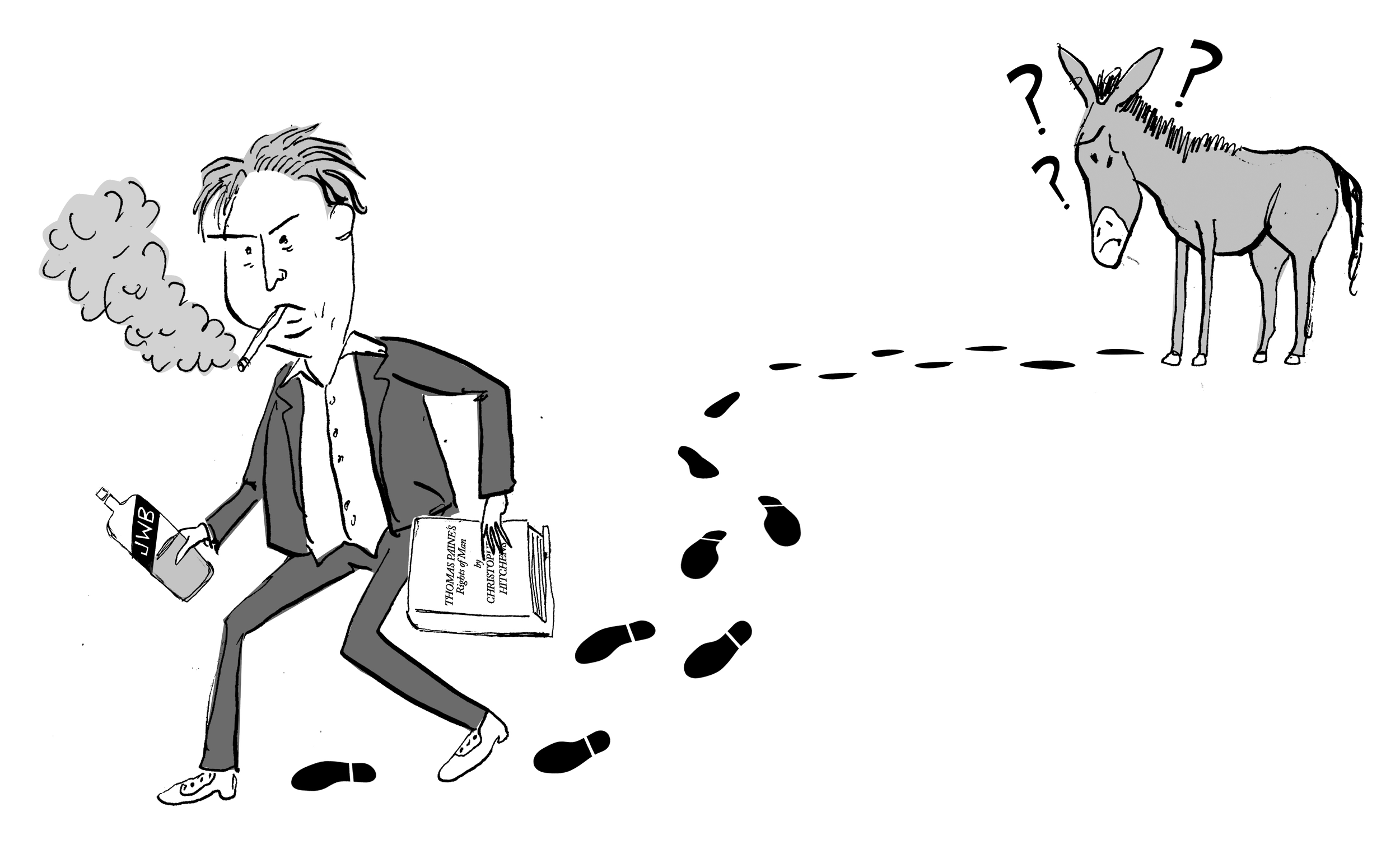

In the introduction to his 1993 collection of essays For the Sake of Argument, Christopher Hitchens affirmed his commitment to the left: “Everyone has to descend or degenerate from some species of tradition,” he wrote, “and this is mine.” Hitchens’s political trajectory is often presented as a story of left-wing degeneration. His career was “something unique in natural history,” as former Labour MP George Galloway put it: “The first ever metamorphosis from a butterfly back into a slug.” After Hitchens abandoned socialism and all other formal political allegiances, his critics say he became a fulminating reactionary, a neocon warmonger, and a dreary cliché: the defector, the sellout, the predictable left-wing apostate.

The standard left-wing narrative about Hitchens is that he exchanged his socialism for some species of neoconservatism. After many years as a left-wing dissident in Washington, DC, he took the side of the U.S. government when it launched the most maligned war since Vietnam. Sure, he said a few sensible things about the excesses and contradictions of capitalism in his days as a Marxist, established himself as the most lacerating critic of U.S. foreign policy in the American media, and did more to put an asterisk next to Henry Kissinger’s reputation than just about any other writer. But this long radical resume is now just a footnote in what many on the left view as a chronicle of moral and political derangement—the once-great left-wing polemicist becoming an apologist for the American empire. On this view, if the left has anything to learn from Hitchens, it’s strictly cautionary.

From socialist to neocon. It was an irresistible headline because it’s a story that has been told over and over again—according to many authorities on the left, butterflies have been morphing back into slugs since the dawn of natural history. The novelist Julian Barnes called this phenomenon the “ritual shuffle to the right.” Richard Seymour, who wrote a book-length attack on Hitchens, says his subject belongs to a “recognisable type: a left-wing defector with a soft spot for empire.” Irving Kristol’s famous description of a neoconservative is a liberal who has been “mugged by reality,” which implies a reluctant and grudging transition from idealism to safe and boring pragmatism. By presenting Hitchens as a tedious archetype, hobbling away from radicalism and toward some inevitable reactionary terminus, his opponents didn’t have to contend with his arguments or confront the potentially destabilizing fact that some of his principles called their own into question.

Hitchens didn’t make it easy on the apostate hunters. To many, he was a “coarser version of Norman Podhoretz” when he talked about Iraq and a radical humanist truth-teller when he went on Fox News to lambaste the Christian right: “If you gave Falwell an enema,” he told Sean Hannity the day after Jerry Falwell’s death, “he could be buried in a matchbox.” Then he gave Islam the same treatment, and he was suddenly a drooling neocon again. He called for the removal of Saddam Hussein and the arrest of Kissinger at the same time. He endorsed the War on Terror but condemned waterboarding and signed his name to an American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) lawsuit against the National Security Agency (NSA) for warrantless wiretapping. He defied easy categorization: a socialist who spurned ideology, an internationalist who became a patriot, a man of the left who was reviled by the left.

The left isn’t a single amorphous entity—it’s a vast constellation of (often conflicting) ideas and principles. Hitchens’s style of left-wing radicalism is now out of fashion, but it has a long and venerable history: George Orwell’s unwavering opposition to totalitarianism and censorship, Bayard Rustin’s advocacy for universal civil rights without appealing to tribalism and identity politics, the post-communist anti-totalitarianism that emerged on the European left in the second half of the twentieth century. Hitchens described himself as a “First Amendment absolutist,” an echo of historic left-wing struggles for free expression—from Eugene V. Debs’s assertion of his right to dissent during World War I to the Berkeley Free Speech Movement. Hitchens argued that unfettered free speech and inquiry would always make civil society stronger. When he wrote the introduction to For the Sake of Argument in 1993, he had a specific left-wing tradition in mind: the left of Orwell and Victor Serge and C.L.R. James, which simultaneously opposed Stalinism, fascism, and imperialism in the twentieth century, and which stood for “individual and collective emancipation, self-determination and internationalism.”

Hitchens believed “politics is division by definition,” but his most fundamental political and moral conviction was universalism. He loathed nationalism and argued that the international system should be built around a “common standard for justice and ethics”—a standard that should apply to Kissinger just as it should apply to Slobodan Milošević and Saddam Hussein. He believed in the concept of global citizenship, which is why he firmly supported international institutions like the European Union. He didn’t just despise religion because he regarded it as a form of totalitarianism—he also recognized that it’s an infinitely replenishable wellspring of tribal hatred. He opposed identity politics because he didn’t think our social and civic lives should be reduced to rigid categories based on melanin, X chromosomes, and sexuality. He recognized that the Enlightenment values of individual rights, freedom of expression and conscience, humanism, pluralism, and democracy are universal—they provide the most stable, just, and rational foundation for any civil society, whether they’re observed in America or Europe or Iraq. And yes, he argued that these values are for export.

Hitchens believed in universal human rights. This is why, at a time when his comrades were still manning the barricades against the “imperial” West after the Cold War, he argued that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization should intervene to stop a genocidal assault on Bosnia. It’s why he argued that American power could be used to defend human rights and promote democracy. As many on the Western left built their politics around incessant condemnations of their own societies as racist, exploitative, oligarchic, and imperialistic, Hitchens recognized the difference between self-criticism and self-flagellation.

One of the reasons Orwell accumulated many left-wing enemies was the fact that his criticisms of his own “side” were grounded in authentic left-wing principles. When he argued that many socialists had no connection to or understanding of the actual working class in Britain, the observation stung because it was true. Orwell’s arguments continue to sting today. In his 1945 essay “Notes on Nationalism,” Orwell criticized the left-wing intellectuals who enjoy “seeing their own country humiliated” and “follow the principle that any faction backed by Britain must be in the wrong.” Among some of these intellectuals, Orwell wrote: “One finds that they do not by any means express impartial disapproval but are directed almost entirely against Britain and the United States. Moreover they do not as a rule condemn violence as such, but only violence used in defence of the western countries.”

Hitchens observed that many on today’s left are motivated by the same principle: “Nothing will make us fight against an evil if that fight forces us to go to the same corner as our own government.” This is a predictable manifestation of what the American political theorist Michael Walzer calls the “default position” of the left: a purportedly “anti-imperialist and anti-militarist” position inclined toward the view that “everything that goes wrong in the world is America’s fault.” The tendency to ignore and rationalize even the most egregious violence and authoritarianism abroad in favor of an obsessive emphasis on the crimes and blunders of Western governments has become a reflex on the left.

Much of the left has been captured by a strange mix of sectarian and authoritarian impulses: a myopic emphasis on identitarianism and group rights over the individual; an orientation toward subjectivity and tribalism over objectivity and universalism; and demands for political orthodoxy enforced by repressive tactics like the suppression of speech. These left-wing pathologies are particularly corrosive today because they give right-wing nationalists and populists on both sides of the Atlantic—whose rise over the past several years has been characterized by hostility to democratic norms and institutions, rampant xenophobia, and other forms of illiberalism—an opportunity to claim that those who oppose them are the true authoritarians.

Hitchens was prescient about the ascendance of right-wing populism in the West, from the emergence of demagogues who exploit cultural grievances and racial resentments to the bitter parochialism of “America First” nationalism. And he understood that the left could only defeat these noxious political forces by rediscovering its best traditions: support for free expression, pluralism, and universalism—the values of the Enlightenment.

The final two decades of Hitchens’s career are regarded as a gross aberration by many of his former political allies—a perception he did little to correct as he became increasingly averse to the direction of the left. He no longer cared what his left-wing contemporaries thought of him or what superficial labels they used to describe his politics. Hitchens closes Why Orwell Matters with the following observation: “What he [Orwell] illustrates, by his commitment to language as the partner of truth, is that ‘views’ do not really count; that it matters not what you think, but how you think; and that politics are relatively unimportant, while principles have a way of enduring, as do the few irreducible individuals who maintain allegiance to them.”

Today’s left should learn from Hitchens.

This essay is excerpted from How Hitchens Can Save the Left: Rediscovering Fearless Liberalism in an Age of Counter-Enlightenment, which is available for purchase at these paid links: Amazon, Bookshop, and Pitchstone.

Matt Johnson writes for Haaretz, Quillette, The Bulwark, Arc Digital, and many other publications.