A Principled Approach for Reforming “Woke” Schools, Universities, and Workplaces

To see Critical Social Justice (i.e., “wokeness”) out of our institutions without replacing it with anything else authoritarian or undermining academic freedom, artistic freedom, and freedom of belief and speech generally, we will need both principled big-picture thinking and specific policies. While it clearly seems to some that addressing the problem of authoritarian impositions of Critical Social Justice might be more easily achieved by forbidding the Critical Social Justice ideas rather than the authoritarianism, this position is not supported by evidence. Banning ideas simply doesn’t work; it also undermines the foundations of liberal democracies. Banning the authoritarian imposition of ideas, on the other hand, has a much better track record of success and upholds those all-important foundations. The concept of “secularism,” in which religious believers have the right to their beliefs but no right to institutionalize them or impose them on other people, is something the United States does particularly well, and there is no reason to think it and other countries could not expand this concept to political ideologies too.

We must take direct action now to reform ideologically captured institutions using the precedent of secularism. I have worked with numerous employers to reform their policies and advise on their training programs, so I am most qualified to speak specifically to that issue, but I shall also offer some thoughts on the issue of schools and universities based on general principles and the insights of parents, teachers, students, and academics who came to Counterweight.

Schools

Schools should not teach any political philosophy as true, just as they should not teach any religion as true (note: the U.S. school system offers perhaps the strongest model for this, as state schools in many countries, including the United Kingdom, do teach one religion as true). With younger children, there is frequently no need to teach any political or philosophical framework at all. A focus on primary subjects like math and language alongside a general rule against bullying is generally sufficient. Of course, teachers will need to respond to any racist, sexist, or homophobic bullying specifically, and policies will be needed on how to do this. No teacher should be encouraging a child to share any thoughts they might be having on their sexuality or gender expression, and any concerns a teacher might have about comments made by a child related to either should be reported to the same professionals who already support children showing signs of anxiety, distress, or difficulties at home. Teachers are not psychologists trained to deal with difficulties experienced by children in relation to their sexuality or sense of gender, and the poor current standards of such services are a separate issue to be dealt with and not a reason for any teacher to feel she must attempt amateur therapizing or an excuse for her to do so based on her own beliefs. It is essential that removing any expectation of sexuality or gender therapy from schools does not tip too far in the other direction and cause any child to feel that they must hide the fact that their parents are the same sex or perform any conventional gender roles.

As children get older, they will need to encounter political views, probably first in history and then in more advanced studies like sociology and media, and they will need to feel confident to think critically about them and begin to form opinions. Schools should make the same effort they do with religions to teach about political views without teaching them as true. While finding the right balance in any curriculum will always be difficult, certain stances are recognizably political and should always be framed as opinion if discussed at all depending on the age of the students, such as “All white people are racist,” “Anti-discrimination law is forced association,” “Property is theft,” “Taxation is theft,” “Everybody has a gender identity,” “Gender roles are good and must correspond with biological sex,” “We live in a patriarchy,” and “We don’t live in a patriarchy but we should.” Teaching children these as true should be as clearly understood to be as wrong as teaching them that “Jesus is the son of God,” “Jews are God’s chosen people,” or “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is his prophet.” Parents must be able to report any concerns they have about ideologically biased teaching and expect to be taken seriously, but they must also not have the power to pressure schools into adopting their own political bias.

Universities

Publicly funded universities must be reformed to make them fit for their purpose of knowledge production, which requires the active mitigation of ideological bias. Methods for doing this will vary across disciplines. While academics in the hard sciences and many of the social sciences must try to eliminate as much bias as possible by adhering to scientific methods specifically set up to minimize human bias or error, this is not the case in all subjects. Many disciplines within the humanities and social sciences, particularly, benefit from scholars arguing from a variety of political, philosophical, or ideological standpoints. This benefit is, of course, lost if they all adhere to the same set of biases or feel under pressure to pretend they do. Universities should be able to show that they have taken steps to foster viewpoint diversity and balance their academic faculty for the benefit of rigorous collaborative research and their students. While certain subjects tend to attract more scholars on the political left, if a political science department has no political scientists who are conservative, liberal, or libertarian, it should be expected to show the efforts it has made to recruit some and also what those professors and instructors in the department are doing to ensure they provide their students with counterviews to their own perspectives.

There should be an expectation of academics that they will engage with critique from colleagues working in the same area but from a different ideological standpoint. There should be no subjects that are “not up for debate” in a university. In the area of social justice, differences in, for example, analyses of disparities in society can be regarded in the same light as competing hypotheses. This is particularly important within scholarship that seeks to better understand our social reality for the purpose of addressing disadvantage faced by various groups. As biometrician Darryl I. MacKenzie and his coauthors explain, speaking from species and community ecology, “Science can be viewed as a process used to discriminate among competing hypotheses about system behavior, that is, discriminating among different ideas about how the world, or a part of it, works.” They go on,

The key step in science then involves the confrontation of these model-based predictions with the relevant components of the real-world system. . . . Confidence increases for those models (and hence those underlying hypotheses) whose predictions match observed system behavior well and decreases for models that do a poor job of predicting.

This basic scientific principle holds true for any rigorous scholarship that seeks to obtain factual knowledge about the workings of the world. While humans are a particularly messy and complicated part of the world and our behaviors can be hard to measure and interpret directly, predictions can still be made and compared to measurements from the real world. This has been done with the predictions of Critical Social Justice, and it is not shaping up very well. It is essential that other hypotheses are also able to be raised and tested. It is quite possible that Critical Social Justice does have valuable insights to offer because even when general theories do not stand up to scrutiny, specific hypotheses within them may still do so, but we cannot know this unless the scholars accept that critique and comparison with both competing hypotheses and empirical measurements of social reality can be legitimate and respond to any critique or criticism of their work with counterevidence and counterarguments.

Workplaces

It is utterly reasonable and, indeed, necessary for there to be workplace rules against displaying prejudice or hostility to people or discriminating against them because of their race, sex, sexuality, nationality, religion (or lack of religion), gender identity, disability, weight, etc. What is illiberal is imposing one ideological framework for doing so upon everybody and requiring them to affirm it to keep their job. A truly inclusive workplace would accept that there are many moral frameworks from which it is possible to oppose bigotry and that diversity includes diversity of viewpoints.

Taking racism as an example, liberals might say that evaluating people by their racial category rather than as individuals is likely to result in both factual error and illiberal stereotyping. They may also say that the best way to combat racism is by opposing evaluating others by their race consistently. Socialists might say that social class is the major cause of inequality and factor race into that framework while arguing that a primary focus on race divides the working class and makes remedying class-caused disparities harder. Critical Social Justice advocates might say that opposing racism requires all of society to become aware of the unconscious racial biases that they believe we are all socialized into and that we should work to dismantle them. Meanwhile, conservatives or libertarians might argue that people need to take personal responsibility not only to treat all races equally but also for much of their own success and that placing too much responsibility on society is disempowering to individuals. Somebody whose primary ethical framework is religious might argue that racism is wrong because we are all God’s creations or draw on theological texts from their specific faith tradition as grounds for opposing racism. It is likely that most people would simply say that racism is stupid and hurtful and that we should be thoughtful and kind to our fellow humans generally, not only our work colleagues. Some people may prefer not to share their views at all, and this position must be respected as well because it is illiberal for an employer to demand to know the inner values, thoughts, and beliefs of employees.

Recommendations for Workplace Policies

There are genuinely inclusive and productive ways to address bias in the workplace. Based on my work with employers and my years-long research on the impact of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs, I have found that policies generally work best when they are (1) kept simple, (2) in accordance with any local antidiscrimination law, (3) clear that people are entitled to oppose discrimination and prejudice in a way that aligns with their own personal political, philosophical, and religious beliefs, and (4) based on traditional liberal principles. Specifically, employers might do the following:

Make a general statement of adherence to relevant antidiscrimination law. Such laws typically involve straightforward opposition to discrimination on the grounds of characteristics like race, sex, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability or genetic information, pregnancy, and marital status. Antidiscrimination law in some countries explicitly includes political beliefs or philosophical beliefs, but some do not and some vary from region to region.

Make a commitment to treat all employees with equal courtesy and consideration and to refrain from any prejudice or hostility on the grounds of the above and ask all employees to do the same.

Take care to specifically state that employees are free to oppose discrimination on the grounds of their own political, philosophical, or religious beliefs, which they need not share publicly.

Make a commitment to not impose any religious, philosophical, or political beliefs on others at work and require employees to do the same.

Make a commitment to not tell employees that their particular religious, philosophical, or political beliefs are false or immoral and ask employees to do the same when at work.

Make clear that any demands that the company adopt any particular religious, philosophical, or political belief that goes beyond existing antidiscrimination law or company policy and that is contradictory to other lawful religious, philosophical, or political beliefs will be rejected.

Make clear that these statements and commitments are taken very seriously and that any contravention of them will lead to appropriate disciplinary action.

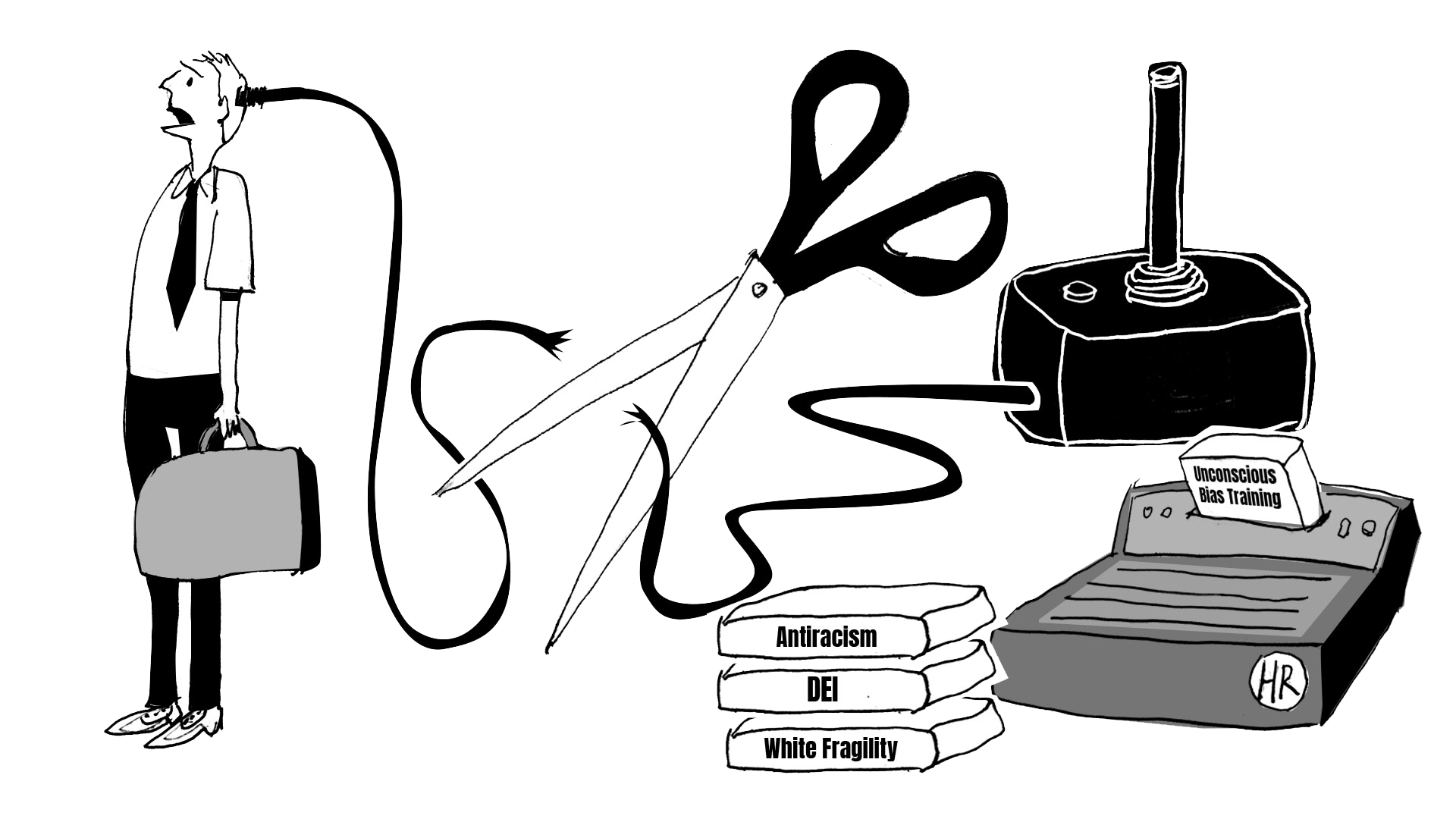

Recommendations for Training

When it comes to training, I am often asked if I know of any liberal DEI training programs. I do not know of any and there’s a good reason for that: liberals don’t tend to train people in what they should think. They require people not to engage in prejudiced or discriminatory behavior that harms, disadvantages, or denies the rights of others while leaving them to comply with this from whatever ethical framework they hold. However, when we look at elements of programs that have worked to increase workplace harmony and decrease discrimination, there is a pattern that diverges considerably from the Critical Social Justice approach and is entirely consistent with liberalism. They have these key shared features:

A commitment to voluntary attendance so that people do not feel coerced.

A discussion of the various kinds of biases that might affect a workforce, including ones based on our hardwiring, our cultural expectations, and our individual experiences.

A process that focuses on shared workplace goals.

An avoidance of essentializing or stereotyping any group.

A focus on fostering a sense of belonging and team cohesion rather than difference.

A focus on overall improvement of processes rather than on the presumed biases of problematic individuals due to their identity.

A universal commitment to inclusion—including of white people and men—as part of building a truly diverse workforce.

It might seem odd that these need to be stated as productive ways to go about having a discussion of antidiscrimination policy and reduction of bias in the workplace. Indeed, as sociologists Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev report, “people react negatively to efforts to control them.” But we needn’t review a wide body of organizational research to discover this. Anyone who has ever encountered humans before already knows this to be the case. Similarly, the finding that human bias exists on a universal, cultural, and individual level should come as a surprise to no one. Those are the levels on which humans exist. Do humans respond better when work meetings are relevant to their work? Yes, I expect they do. I am also unsurprised that not essentializing and stereotyping demographics results in fewer essentialist and stereotypical assumptions. And of course an approach that focuses on shared goals and purpose and similarities rather than differences and does not single any demographic out as a problem is going to bring people together better than one which does the opposite. The reason that this all needs to be stated today, however, is because Critical Social Justice has done the opposite of all of this and significantly damaged human relations in the workplace and throughout society.

Seeing the bigger picture and standing by the principles that underlie one’s society is not a weak position but a strong and lasting one. Bad ideas come and go, but liberal democratic ideals can outlast them all. They contain within themselves the tools to defeat bad ideas as long as we stand by the principles that have protected the freedom of belief and speech that enables this.

This essay is excerpted from The Counterweight Handbook: Principled Strategies for Surviving and Defeating Critical Social Justice―at Work, in Schools, and Beyond, which is available for purchase at these paid links: Amazon, Bookshop, and Pitchstone.

Helen Pluckrose is a liberal political and cultural writer and was one of the founders of Counterweight. A participant in the Grievance Studies Affair probe that highlighted problems in Critical Social Justice scholarship, she is the coauthor of Cynical Theories and Social (In)justice and writes at The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain on Substack. She lives in England.